Today, in a largely classless society, the term 'aristocracy' or 'nobility' has little meaning. Dukes, lords and knights have little to do with the lives of ordinary people. Indeed, many view the position of the aristocracy - a privileged few who have inherited, wealth, lands and titles - as vastly unfair, and particularly so historically when the rest of the population lived in poverty. However, during the first world war, and also to some extend in the second, many of the officers in the armed forces were from the nobility.

To us it seems archaic. Why should someone born to privilege be considered able to command a battalion when a member of the lower orders were not? What exactly is it that makes the aristocracy different?

To find the answer we need to go back in history to the feudal system where European aristocracy had its roots.

The word 'aristocracy' comes from the Greek, the product of the thinking of philosophers Plato and Aristotle. It literally means 'rule of the few best' that is the morally and intellectually superior governing the interests of the entire population.

In England during the Middle Ages, the King owned the whole country. However, as one man, he could not govern the whole lot on his own. So he conferred land or 'manors' on certain ones known as 'barons' or lords. Hence the term 'lord of the manor'. Each baron had to swear allegiance to the King, to fight for him, raise an army for him, and also pay him rent for his manor. He also gave the king advice, thus helping him to govern.

In turn the barons had knights and fiefs and gave them manors. The knights supported and served the lords and fought for them for between forty and sixty days a year. Beneath the knights were the serfs or villeins the ordinary people, who served the knights, worked the land, paid rent in money and kind to the knights, and the men of which served as soldiers when required. In turn the peasants were allowed land to live on and work, and were given firewood from the common and grazing rights and so on.

The landowner was responsible for his people, particularly for law and order, the dispensing of justice. In times of famine, the landowner should see that his people survived. He was also the justice of the peace. It was a practical system which seemed to work when the 'lord' was a fair and just man. If he were not, then of course it was open to abuse.

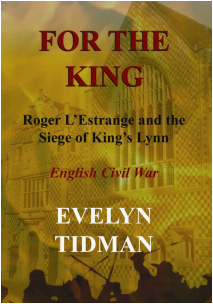

This system of government continued through the centuries and the King continued to grant lands and new titles to men who had assisted him. By the seventeenth century, the system had evolved into the government of the land, the aristocracy having the right to sit in the House of Lords in Parliament. However, just as formerly, each 'lord' was responsible for his people. In my book FOR THE KING when Sir Hamon L'Estrange was arrested on the count of treason and paraded before the people of King's Lynn for them to choose whether to send him to stand trial, or for them to declare for the King they said:

‘What be you thinking, Tom Gurlin? Send Sir ’Ammon to Wisbech? Sir ’Ammon whose succoured us in distress, fed our children when we lacked bread? We hin’t that lacking in gratitude. Our little’uns hin’t going to blush with shame in remembrance of this day!’ Whilst the speech (Norfolk dialect) is fictional, the sentiments are recorded history. It shows how ordinary people viewed their 'lords'.

In times of war, the common people looked to their 'lords' for direction and protection. During the English Civil War, when the New Model Army under Cromwell used violence to keep people in order, the people looked to their 'lords' to solve the problem. They trusted them to lead them into battle, and viewed them as men educated for that very task. In turn their gentry directed them, but also fed, armed and clothed them, and paid them wages out of their own pockets, compensating them for their loss of earnings while on the campaign.

Where the common people did not have the contacts, nor the understanding of the politics going on at the top, the aristocracy did. They were at the forefront of policies, of law-making, and they knew each other. A network of the nobility stretched across the land strengthened by marriage ties. Common people accepted that they did not have the education, nor the contacts to understand politics or laws. They left that to the nobility who were educated for the job. Which is why such schools as Eton and Harrow came into being, and why only the sons of the gentry could get into University. One of the favoured subjects of education was Law. The aristocracy knew how the system worked.

Of course, no society is perfect. And the nobility under the feudal system were far from perfect. But when decent men acted honourably towards their people, society benefited.

But the English Civil War challenged the old order. With the murder of the King, England changed forever, and began the march to the political system we have today. When a jumped-up commoner called Oliver Cromwell became Lord Protector instead of the King, it changed the role of the monarchy and aristocracy. Today with education to the highest level is available to every person in the land, the role of the aristocracy has been eroded, has become out-dated. The Lord of the Manor no longer has any control over the common people. Unless, of course, he happens to be a member of the government . . .

Roger L'Estrange and the Siege of King's Lynn

Join in the action of this swashbuckling adventure!

1643 and a town in Norfolk becomes the focus of Parliament when the people declare for the King. When each side views the other as traitors fit for execution, who can you trust?

- Drama in a town under pressure, surrounded by a brutal enemy.

- Danger from false friends as well as enemies.

- Adventure as Roger risks his life to rescue the town.

- Romance as Royalist Roger finds forbidden love with Puritan Ruth.

OUT NOW ON KINDLE AND IN PRINT!

CLICK HERE TO BUY

RSS Feed

RSS Feed