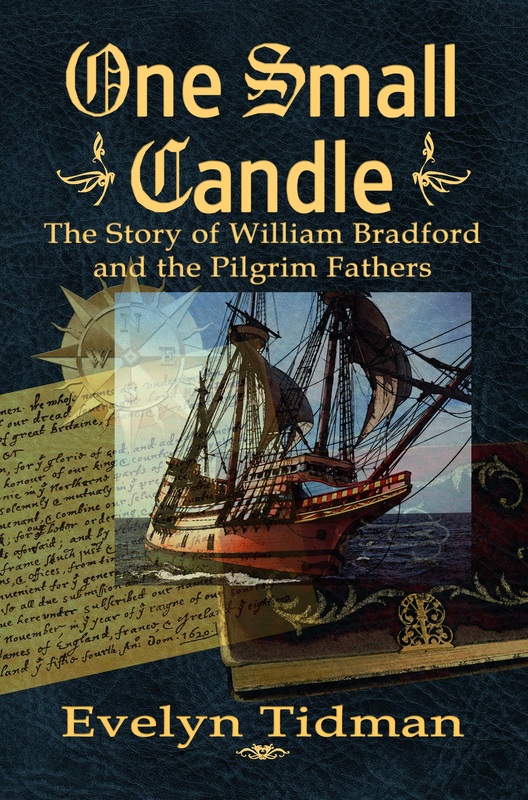

The root lies in the translation of the Bible into the vernacular languages of the day. Originally written in Hebrew for the Old Testament (with a smattering of Aramaic) and Greek for the New, translation became necessary for the scriptures to reach a wider audience. Indeed, the first translation of the scriptures was of portions of the Old Testament into Greek, this before the birth of Jesus Christ. The reason was that Greek had become the common language through the empire built by Alexander the Great. In the time of the Roman empire, however, and round about the end of the first century, Latin had taken over as the common language of the people. So the scriptures were translated into Latin. Actually there were several Latin translations, but the most widely used came to be called the Latin Vulgate, because it was common, or vulgar Latin.

However, as time went on and language changed again, and people began to speak English and French and German, you would think that the scriptures would again be translated into those languages. But the Catholic Church, which had risen in the fourth century CE refused to sanction the translation. For example, in 1199 Pope Innocent III condemned French translations of the Psalms, the gospels and the letters of the Apostle Paul. Cistercian monks burned any copies that they found. In 1229: “We forbid the laity to have in their possession any copy of the books of the Old and New Testament, except the Psalter, and such portions of them as are contained in the Breviary, or the Hours of the Blessed Virgin; and we most strictly forbid even these works in the vulgar tongue.” - Council of Toulouse, France, Canon 14.

It was deemed that people would 'become confused' by reading the Bible for themselves. So for centuries the Bible stayed in Latin, and only those versed in that language could read it at all. For the most part that was priests and monks and those schooled by them. It meant that common people had to accept what they were told by the priests, whether right or wrong. The Church had complete control.

When we come to the Middle Ages a few brave souls, scholars, sought to translate the Bible into different languages. John Wycliffe, Miles Coverdale and William Tyndale were among those translating into English, while on the Continent other scholars worked on vernacular translations. William Tyndale famously said to a priest: "If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the scripture than thou dost.” But Tyndale was persecuted. He fled to the Continent, but was denounced by a priest, and brought back to England where he was burned at the stake for heresy (after being strangled first) in 1536. His last words were: 'Lord, open the King of England's eyes.' So great was the opposition to Tyndale's translation of the Bible that very few copies remain - in the British Museum there are just a few pages.

Nevertheless, the cat was out of the bag. As people read the scriptures for themselves, they could see that what they had been taught was in error. Famously on October 31, 1517 Martin Luther had nailed his theses to the door of the castle church at Wittenberg, Saxony protesting at the sale of indulgences, kick-starting the Reformation. While Henry VIII was on the throne, the Reformation gathered pace. Ideas began to flow freely, although the Church did its best to stifle it. Religion was the most hotly debated topic in the taverns and any meeting places. Subjects such as Predestination, should there be clergy? Who was God? and so on were matters of great concern. Then Henry VIII famously took England out of the grip of Rome, became head of the English Church and dissolved all the monasteries. The Reformation gathered pace.

When Henry's daughter Mary Tudor succeeded her brother Edward VI to the throne, however, she tried to force England back to Rome. Known as Bloody Mary for her Inquisitional ideas of burning people at the stake for 'heresy', under her rule terror reigned in Britain. But her successor Elizabeth turned the tables and Britain was once again free of Rome.

The more people read the Bible, the more they wanted change. The Church of England, in the view of many, did not go far enough. They were episcopalian, that is, their hierarchy consisted of priests. The Presbyterians, however, had church government by elders, or presbyters, because they said that there was only one high priest - Jesus. The Puritans wanted to change the Church of England, and worked from within the church to change it. The Separatists decided that was a bad idea, and the Church wouldn't change anyway, so they - well - separated.

From this confusion, came other groups. The Methodists, the Quakers, the Mennonites, the Baptists, Congregationalists and so on. All of them were looking at the scriptures, and deciding that their contemporaries were wrong, and that they were right. Tracts and books and booklets flowed off the different presses, as different scholars put their views and counterviews for one argument or another. All were looking for truth, but the truth was still very difficult to find.

In the middle of all this, the Church of England, by now the Established Church with the sovereign firmly planted at its head, wanted to keep a grip on things. The bishops advised King James I as to doctrine. He had been brought up in Scotland, and his mother was Mary Queen of Scots, beheaded on Elizabeth's orders or course, and she had been staunchly Catholic. This upbringing had an influence on James who leaned towards Catholicism.

With all this religious confusion, James needed to solidify his domain. Laws were brought in. Every person in England was required to go to their parish church on a Sunday or be liable to the Ecclesiastical court. Well that was fine and dandy if you were an Anglican, but if you did not agree with that, and the Separatists did not, then immediately you were in trouble. And the penalties could be severe - imprisonment or even execution. The Separatists found themselves spied on. Meetings were raided, as were homes. Worse, if you dared to disagree with the Church on doctrine, you disagreed with the King, for he was head of the Church. And that was treason. And treason brought the death penalty.

The only way the Separatists could actually do their own thing was to leave England. But that required permission from the King, and that was not going to happen. The King and church, strangely, did not want them to leave. Why not? From the point of view of the King and the Anglican Church it would be better to persuade the dissidents to come back to the church rather than for them to go away and continue in their 'error'. So they were denied permission. But they did leave, clandestinely, and sailed for Holland, which country allowed freedom of worship.

Later, when it came to going to America, they again had to get a patent from the King. And again they ran into this opposition. He questioned their representative closely on their beliefs, church government, and particularly whether they believed in a Trinity. The idea of the Trinity was a sticky subject. (The Trinity doctrine is the idea that God is God, Jesus is God and the Holy Spirit is God, but there are not three gods, only one, the three-in-one doctrine.) The Separatists (and others) did not believe a Trinity, viewing it as unscriptural. But to say so was treason and punishable by death. They hedged and demurred, but at last they got their patent. But it was touch and go.

Of course, the Reformation eventually brought the English Civil War, with Puritans against the Royalists, although there were many political issues involved. And since then there has been little major religious persecution, most of the English thinking that how the other bloke worships is his own business, although certain groups have suffered on a personal level in England.

Of the Pilgrims, when they arrived in America, they drew up the Mayflower Compact which guaranteed freedom of worship, and on which the American Constitution is based. They certainly did not want a repeat performance of the atrocities carried out in the name of religion in England.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed