Hunstanton Hall. The 14th century gatehouse with solar over is in the centre in red brick. Behind it, to form a quadrangle, would have been the old medieval hall which burnt down in 1850.

Hunstanton Hall. The 14th century gatehouse with solar over is in the centre in red brick. Behind it, to form a quadrangle, would have been the old medieval hall which burnt down in 1850. In Hunstanton the name L'Estrange or Le Strange, which is the Victorian spelling, is well known. It was Henry Styleman Le Strange who built the Victorian seaside resort town of [new] Hunstanton just a mile or so along the coast, making the original Hunstanton end up with the prefix 'Old'. We Have the Le Strange hotel, and Le Strange terrace. Le Strange owned the mussel beds just off the beach, as a sign there proclaims. Now intrigued, I decided to go digging in the library.

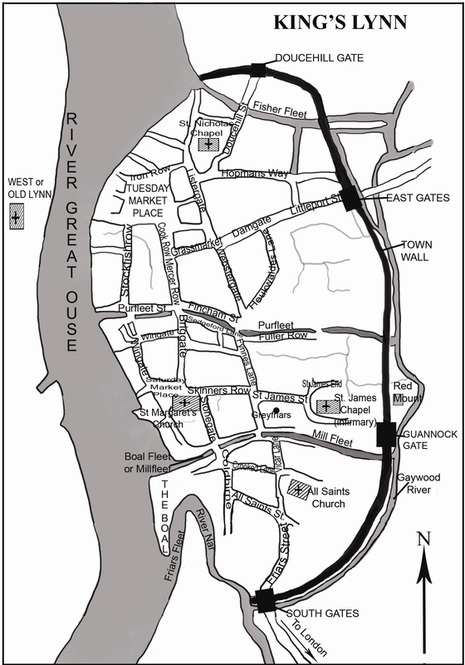

What I discovered was the amazing story of the family during the Civil War, how Sir Hamon L'Estrange, the lord of the manor, managed to instigate a siege of the nearby town of King's Lynn by the Parliamentary army. That was interesting enough, but it was the youngest son of Sir Hamon, Roger, who caught my attention.

It turned out that not only was Roger (at twenty-seven) fighting with his father during the siege, but he also tried to re-take King's Lynn for the King later. After a spell in exile on the continent with other Cavaliers, he returned to England and began a career as a pamphleteer promoting the restoration of the monarchy and attacking Commonwealth writers, most notably, John Milton and his Paradise Lost. He was granted the position of Surveyor of the Imprimery (Printing Press) and then Licencer of the Press from which position he could act as a censor, which he did with a will, taking the position of confirmed Royalist and Anglican. He was close to Charles II, and James II who gave him a knighthood. He was involved in the Titus Oates affair, and at one time was so hated by the people of London that they burnt him in effigy! At one stage he went into exile again until the heat cooled.

Personally, he was 'a man of good wit and a fancy luxuriant, and of an enterprising nature' according to Edward Hyde, the first Earl of Clarendon. Witty he certainly was, as his phenomenal output of writing show us. Often sarcastic, sometimes downright caustic, and he never pulled his punches.

If you are interested you can find some of his works on Amazon and his famous quotes by Googling his name.

He died of a stroke at the age of eighty-nine.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed